Thinking ‘Liturgy First’ (and Music Second)

I am of the firm mind that church musicians must think in terms of liturgy before music. To put it simply: music must serve the Mass; the Mass is not merely a pretty liturgical frame for your music making.

This thinking has real-world consequences for how one plans a parish’s Masses. Mothers’ & Fathers’ Day, Secular “Holidays” [which are rarely ‘Holy Days’], parish festivals, and much besides, should not take precedence over the actual liturgy of the day. The liturgy is comprised of texts/prayers/propers which are prescribed for us, and are not matters of whim, and these collections of texts stand on their own, apart from worldly externals.

“Music must serve the Mass; the Mass is not merely a pretty liturgical frame for your music making.”

Every year, it is very common to see American churches overcrowd their Masses with “Patriotic Hymns” (more on this later) on the Sunday that is closest to July 4th, America’s “Independence Day”.

While it is a virtue to have pride for your fatherland, one must draw a careful distinction between a Sunday Mass (this year, the 14th Sunday in Ordinary Time) versus a dedicated Mass of Thanksgiving for the founding of America which actually takes place on July 4th for that express purpose.

As alluded to above, one mistake many music ministers make is to treat the nearest Sunday to 7/4 as “July 4th Sunday”. The fact of the matter is, July 4th is not a liturgical day. Some people see patriotic hymns as harmless, but let me pose this hypothetical: how would an Austrian respond if you told them they should sing Austrian patriotic hymns on the 14th Sunday in Ordinary Time? Or a Frenchman? They are very likely to respond to your proposition with a look of confusion—and with good reason. This response makes sense in when one considers that the Mass is a universal in the church, bound by a religious calendar, not a secular one.

“This Sunday is the 14th Sunday in Ordinary time,

not ‘July 4th Sunday’.”

While it is true that certain days are important (and therefore celebrated) in different ways by different cultures (each parish’s Saint day is a Solemnity, for instance, and every country has a Patronal Saint, etc. etc.) those days which are officially marked by the liturgical calendar have a proper liturgical context. Secular days—however meaningful they may be—do not.

This is not to make the claim that such special days should not be marked by Masses. The treatment of a Mass of Thanksgiving on July 4th itself, with the express intent of marking the date can be treated wholly differently from how one would treat the nearest Sunday. In the case of a dedicated Mass, an abundance of patriotic hymns is perfectly reasonable and such an abundance has a proper context.

Speaking of context, another mistake music directors make is to schedule perfectly fine hymns during perfectly wrong moments. Take the ubiquitous Joyful, Joyful, We Adore Thee. This works best as a recessional, although it can make an acceptable entrance hymn; that said I would never schedule it during communion, since it is at odds with that moment in the liturgy. It is a loud, borderline bombastic hymn, which utterly disrupts a prayerful atmosphere during communion. Such an example proves that context both in terms of theme of liturgy and placement play a part in the success of any given hymn.

Relative to the purpose of this article, we must now return to the issue of what constitutes a proper “Patriotic Hymn”. To put it plainly, there are a number of songs in many hymnals which would more properly qualify as secular anthems than hymns, properly speaking. For instance, if the fourth verse of My Country ‘Tis of Thee was omitted (for timing, perhaps) you would be left with lyrics which merely praised our country but not our Creator, and offers no prayer:

My country 'tis of thee,

Sweet land of liberty,

Of thee I sing;

Land where my fathers died,

Land of the pilgrim's pride,

From ev'ry mountain side

Let freedom ring.

My native country, thee—

Land of the noble, free—

Thy name I love.

I love thy rocks and rills,

Thy woods and templed hills;

My heart with rapture thrills

Like that above.

Let music swell the breeze,

And ring from all the trees

Sweet freedom's song:

Let mortal tongues awake;

Let all that breathe partake;

Let rocks their silence break—

The sound prolong.

This would be (in my humble opinion) a liturgical abuse and affront to our Lord: it would be akin to attending a birthday party and celebrating anything but the anniversarian, who should have otherwise been the center of affections. In this case, verse 4 (which finally addresses God) is essential, however even with its inclusion, the emphasis of the hymn—broadly speaking—is in praise of country, rather than God.

It hardly seems fitting at mass compared to Eternal Father Strong to Save or God of Our Fathers, Whose Almighty Hand whose every verse is either a prayer, petition, or praise. These latter hymns are eminently more liturgical. They are, in a word, actual prayers.

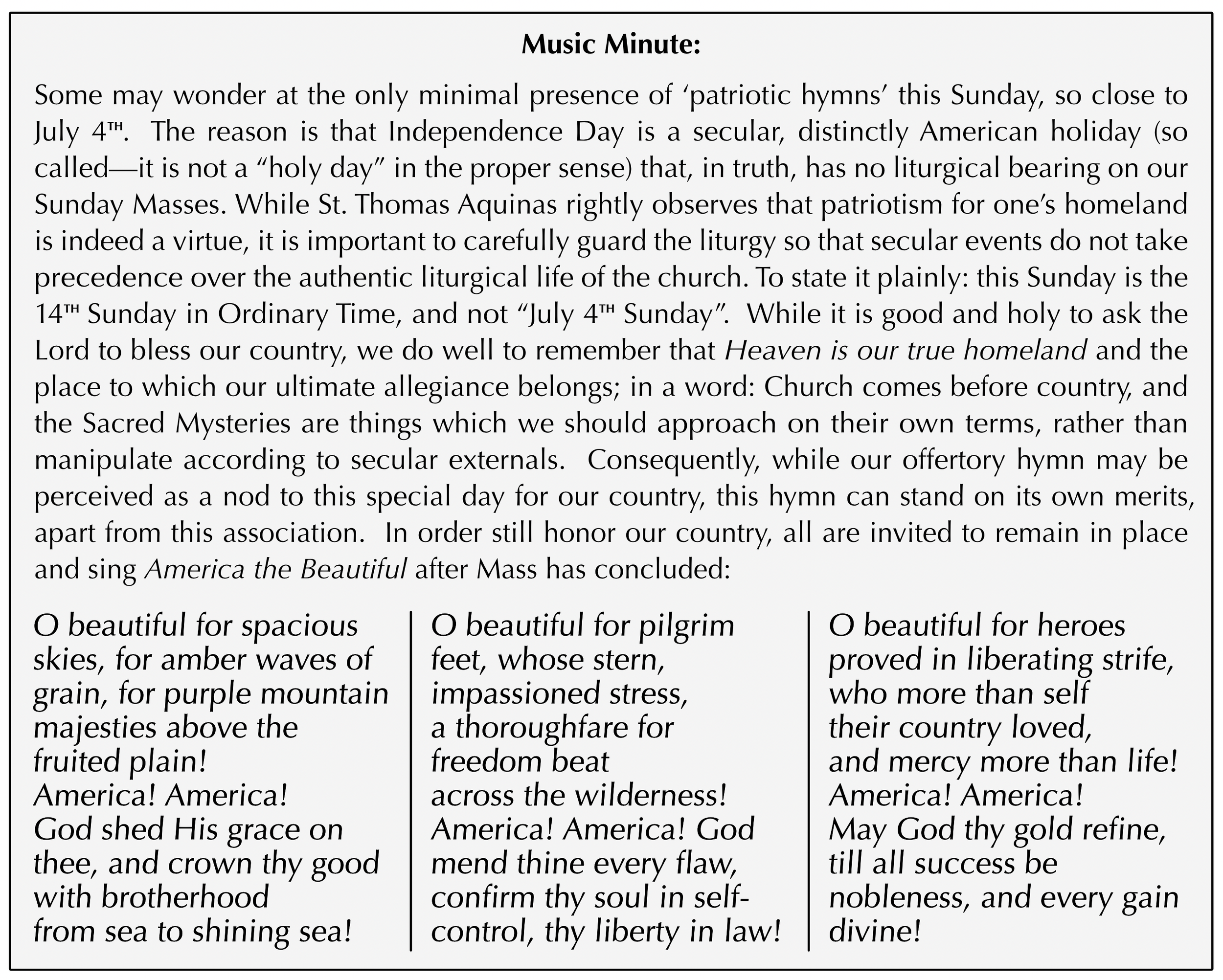

With all of this in mind, I have furnished the follwing “Music Minute” for our parish this weekend, which explains that Mass is “the 14th Sunday in Ordinary Time” and not “July 4th Weekend” whilst still inviting parishioners to remain after Mass to sing America the Beautiful. Being both a prayer and the unofficial-second-national-anthem, this seems an appropriate compromise. We acknowledge and honor our country, without placing the emphasis on it during Mass.

And as an aside, I feel called to mention here a recent interlocutor who rebutted, “Well, we are singing ______ because it’s in the hymnal.” I confess this both humored and saddened me; alas, many main-stream hymnals contain much dross, and—notwithstanding whatever the merits (or lack thereof) of his choice—we do well to remember that hymnals contain things that are not always intended for (or best-suited to) Mass, specifically, since Mass is not the only form of liturgy that takes place in a church. Furthermore, the mere publication of a piece of music in no way means it is endorsed for use, or even the particular use one has in mind. (What’s worse is that an imprimatur or nihil obstat is only as good as those who grant it; I have personally seen instances of works published with approval which contained formal heresy, such as one “Catholic” prayer book with imprimatur from a diocese in New York state which included prayers to the Egyptian demon-god Ra, something so preposterous and odious as to defy belief.) In any case, one would hope that music directors would put more thought into a selection than merely “well, it’s in the hymnal!”

“§20. Religious music should be entirely excluded from all liturgical functions; however, such music may be used in private devotions.”

The preceding quote clearly implies that religious words or sentiments are not sufficient criteria for corporate latria, and that there is a difference between “religious” music and “liturgical” music (a topic for another day).

Hopefully these thoughts stir a desire in the reader to contemplate just how they can be sensitive to liturgy, and not merely music machines who stuff it full of noise music.