A heritage, retold.

David’s psalms are one of the greatest treasures of the Scriptures. Plainchant is one of the greatest treasures of the Church. (And one was literally made for the other.)

The Catholic Mass has incorporated psalmody from the earliest ages; after all: the psalms were even chanted in the Jewish temple. For the last few decades, however, the dignity of the psalms has been diminished through pop-style arrangements which tug at the heart strings more from the emotional style of the music rather than the text it is supposed to breathe life to. Worse still, the pop-styled music is entirely divorced from traditional sacred music and belongs entirely to the secular domain.

As I’ve explored psalmody (and composing settings of the psalms) for the last three years, I have simultaneously been baptized into full, florid Gregorian Plainchant. Living and breathing this heritage has opened my eyes to a whole “new” living tradition, erroneously considered long-dead by so many. Since plainchant is indeed the greatest musical heritage of the Church, and since it has shaped the musical landscape of the liturgy for well over fifteen centuries, (!) it seems only fitting and prudent to recall this heritage when creating new settings of the psalms.

Rooted In Tradition

Plainchant still has much to offer modern composers:

a sober, prayerful spirit

free, text-driven rhythm (unmetered)

modal harmonies

certain recurring patterns in both florid chants as well as reciting tones / cadential formulæ

Rather than imitate secular musical styles, composers can draw on these features that render chant uniquely-suited to sacred liturgy and build upon a living tradition in the Church, rather than part wholesale from it.

Benedictus es, Domine

Blessed are You, O Lord…

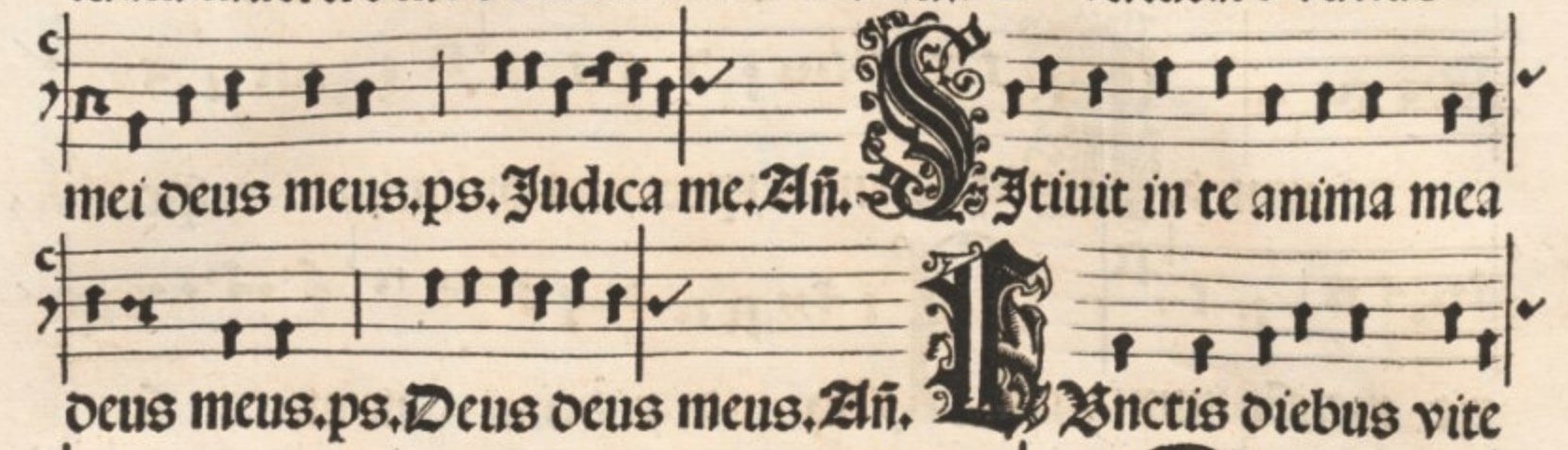

Below you will find an excellent rendition of Benedictus es, Domine, the gradual for Trinity Sunday along with my setting of Psalm 33 for the same feast, but in keeping with the Novus Ordo lectionary. Here you can see that in my setting, the refrain is unmetered—following the natural ebb & flow of the text—and the beginning of the melody directly outlines the beginning the gradual which it replaces.

The verses, arranged in the anglican tradition, are notated in a stemless, idiomatic style: double-whole indicates one chants as long as is necessary according to the text, black notes for passing tones, and stemless half-notes for cadential holds. Notice that the barlines are shared with plainchant as well. This notation allows time to flow freely and naturally, without the need to change the text by constraining it to a metrical impulse or alter word order to fit a rhyming scheme. The result is a natural expression of the text that molds to the general aura of the chant it supplants whilst still permitting the participation of the faithful.

Bonum est Confiteri Domino

Lord, it is good to give thanks to You…

In the case of my setting of Psalm 92, a much more direct approach was taken, even into the verses. This particular gradual lent itself exceptionally well to adaptation. (Click here to read a more in-depth blog post about the approach I took when setting this particular psalm.)

As you can see above, I was able to retain a nearly 1:1 relationship between the refrain and the first measure of the ancient chant. A truly prayerful essence exudes from this method, since the melody is ancient, even if a new harmony was applied to it. The verses are set in a style reminiscent of a psalm tone; the particular contour of “confiteri Domino” lent itself very well to this approach, since its skeletal structure is not dissimilar to tones II & V and the general shape of neumes #10 and #11 (see above) are frequently employed at cadences in countless chants.

As you will see in the video below, the notation for the cantor remains entirely unmetered, complete with reciting tones. This allows for the natural rhythm of the speech to shine forth, with the music only serving to undergird the cantor, and not compete with it. The organ is notated with modern note values, but this serves only to indicate a scale of proportion, not strict time.

Note too that the second half of each verse begins directly on the reciting tone, in a manner similar to chanting the divine office to psalm tones. The end result is, I believe, fantastic, and the prayerful and contemplative aspect of the chant is retained in a way that is uncommon for modern psalm settings.

To see another example of chant adaptation that bears a nearly exact relationship to the original Gregorian antiphon, rather than being derived as shown above, click here.

Conclusions

I believe that it is undeniable that this approach of first consulting the original medieval chants proves superior to simply creating new melodies from scratch. This approach is the future of dignified psalmody.

Chant has many attributes to offer the modern composer that are worthy of imitation and renewal. (click here to see an even longer list of the attributes of plainchant)

Basing new settings upon ancient melodies creates an unparalleled continuity with our liturgical heritage and allows the spirit of the chants to live on in a new way; such an approach also lends a peculiar character to these new compositions that is lacking in many/most contemporary settings but that is essential for liturgical solemnity.